The XYZ University Sustainability Initiative is a comprehensive project aimed at promoting environmental and economic sustainability on campus. We are seeking funding to implement five key goals: a tool library, a textile and fibre bank, a student environmental sustainability champion, a student economic sustainability champion, and makerspace sustainability awards. These goals will provide access to resources, promote repair and maintenance, reduce waste, and increase equitable access, while fostering community-mindedness and encouraging innovation in sustainability. With your support, we can make a significant impact on our campus and community.

ChatGPT in response to the prompt: write a 100 word description for an application for a grant to implement the 5 main goals

Like everyone else lately I’ve been playing with ChatGPT and generally I’ve found the content it creates to be impressive if soulless, but I’ve also mostly used it to write silly poems or to try to convince it to unionize itself. Recently though a friend was telling me how they’ve been using it to get real work done, specifically to create formulaic promotional content like video scripts and tweets from original content.

This got me thinking about how I would do this for my own work. I happened to be working on grant to help the makerspace I run better support sustainability initiatives on campus. Grants tend to be formulaic, with both explicit requirements outlined in the call for proposals and implicit rules about structure and language. I’m not particularly interested in using these tools to generate new content but I’m very interested in the idea I could use them to save time writing structured bureaucratic documents.

What followed has somewhat changed the way I understand the potential utility of these tools, which I now see as useful for refactoring content (and for me that means original content) into a new structures.

This is a quick outline of some of the things I found during an hour or so of playing followed by several hours of reading through the results and trying to understand what ChatGPT produced. You can see the entire series of prompts and responses at this GitHub gist. (note: there is a pirate-themed YouTube video script I forgot to copy that is not included here, but referenced towards the end).

Very briefly: I took 5 draft goals for a grant, and then had ChatGPT work those goals into a number of structures related to the grant proposal. I also had it try to integrate those goals with organizational values and metrics.

Starting with Original Content: 5 Draft Goals

I provided the following original content, asking ChatGPT to simplify the goals and make them more formal. These were draft goals and I don’t claim they are good or will end up in my grant! But I had them in front of me and so that is what I used. The rest of the session was based on this content, along with prompts, and in 2 cases a list of values.

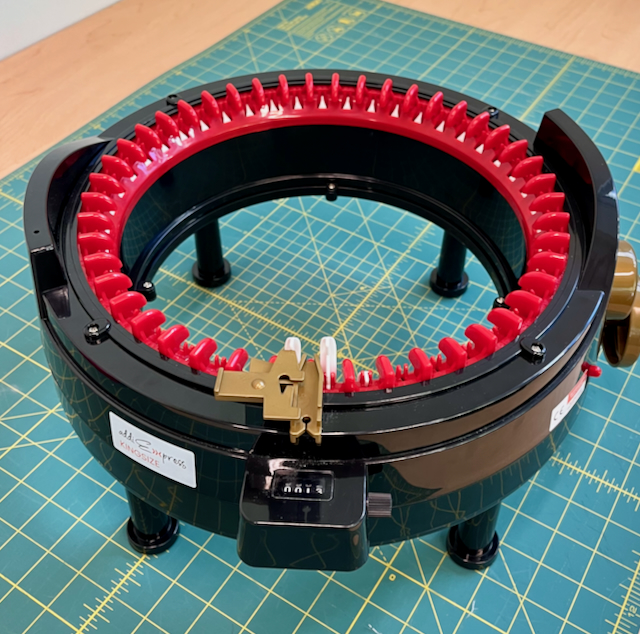

1. Tool Library: Create a tool library of lendable household, automotive, bicycle, and gardening tools. This will reduce waste by promoting repair and maintenance, eliminating duplicate purchasing of items, and increase equitable access to tools.

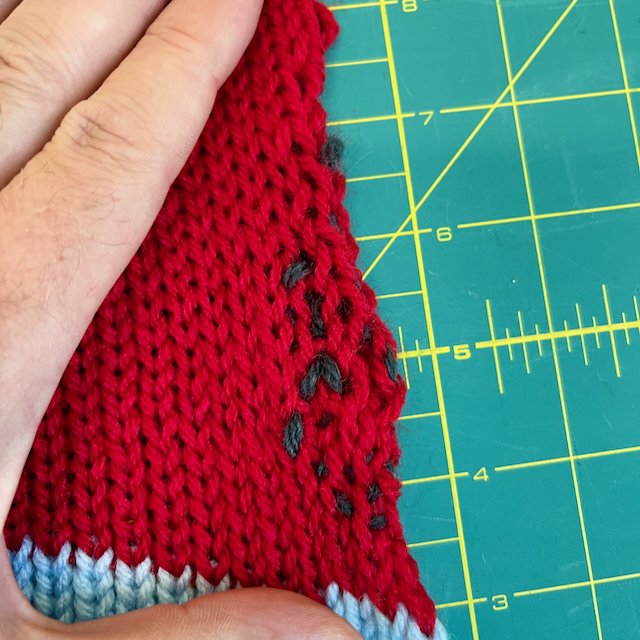

2. Textile and Fibre Bank: Create a donation-based supply of textiles and other fibre materials (cloth, wool, etc.) that can be used to complete assignments, prototype designs, and create and repair clothing and other textiles. This will increase equitable access to these materials and reduce waste by using existing materials instead of purchasing new materials.

3. Student Environmental Sustainability Champion: Hire a student environmental sustainability champion. This student will be responsible for:

1. Running textile fix-it events where people can learn how to modify and repair textiles using Makerspace equipment.

2. Outreach to student clubs promoting the use of the Makerspace for events and sustainability-related activities and learning what other resources and supports are needed.

4. Student Economic Sustainability Champion: Hire a student who will assist the Makerspace in developing relationships and running programming that supports economic sustainability. This student will be responsible for:

1. Outreach to campus and community organizations, including Kamloops Innovation, the School of Business, and student clubs.

2. Helping develop programming such as drop-in hours and workshops for users who want to use the Makerspace for economic sustainability purposes.

5. Makerspace Sustainability Awards: 6 $1000 awards for groups to use to purchase equipment or supplies to use the Makerspace to trial small scale innovations to support economic and environmental sustainability.

ChatGPT is good at generating structure and filling it with content

ChatGPT is surprisingly good at generating formulaic structures and filling them with content. In prompt 2 I ask it to create a one-year implementation timeline and it not only does this, but it even puts items into pretty coherent order, with planning early in the year followed by implementation, and then putting reporting and future planning towards the end. I think it even picked up on the idea that this was for the academic year and put most implementation after September.

November:

- Complete the selection process for the Makerspace Sustainability Awards

- Begin distributing awards to successful applicants

- Begin implementing any necessary adjustments or improvements to the tool library, textile and fibre bank, and student sustainability champion programs

December:

- Continue organizing workshops and training sessions

- Begin planning for the next year's sustainability initiatives

- Prepare a report summarizing the effectiveness and impact of the sustainability initiatives

Similarly, the video scripts (Prompt 6-8) and the budget (Prompt 12) are generated in a perfectly reasonable structure.

Staff member 2: "Our textile and fibre bank is another initiative that supports sustainability. By providing access to donated textiles and fibrous materials, we are reducing waste and promoting equitable access to materials."

Student 1: "I am so excited to be a part of our student environmental sustainability champion program. By running textile fix-it events and promoting the use of the Makerspace for events and sustainability-related activities, we are encouraging repair and maintenance and reducing waste."

Student 2: "And our student economic sustainability champion program is helping us to develop relationships and programming that supports economic sustainability. By encouraging the use of the Makerspace for economic sustainability purposes, we are promoting the use of existing resources and reducing waste."

ChatGPT was also surprisingly good at generating ideas related to the content in the goals. For the timeline prompt it came up with ideas for a planning committee, implementing lending and donation policies, and reporting, all reasonable-sounding and potentially good ideas that weren’t in the original content I provided but are appropriate for an implementation timeline.

In prompt 3 I prompted it to come up with “a plan for measuring each goal’s performance in relation to social and/or economic, and/or ecological benefits”(categories from the grant) and in Prompt 4-5 I asked it to link goals to two sets of institutional values (more on this in a second) and in both cases it generated some potentially good ideas.

2. Textile and Fibre Bank:

- Social Benefits:

- Surveys can be conducted to gather feedback from users on the accessibility and convenience of the textile and fibre bank.

- Number of users can be tracked to evaluate the level of participation in the program.

- Economic Benefits:

- Track the amount of money saved by using donated textiles and fibres instead of purchasing new materials.

- Ecological Benefits:

- Track the amount of waste generated by discarded textiles and fibres that are avoided thanks to the textile and fibre bank.

ChatGPT is a confident and glib bullshitter

In the prompts for measuring performance (3) and linking goals with values (4-5) and the last paragraph of project summary (9) you can see many examples of just how easily ChatGPT generates confident and reasonable-sounding bullshit. It conflates or confuses many of the “values” and creates connections that are glib or nonsensical and wouldn’t stand up to much interrogation.

“All these goals are closely related to the values of inclusiveness, transparency and openness, equity, intellectual freedom, sustainability, stewardship, service and access. By providing access to resources and promoting repair and maintenance, we are reducing waste and promoting equitable access. By promoting environmental and economic sustainability, we are encouraging the use of existing resources and fostering community-mindedness.”

ChatGPT is response to prompt 9: “take all the goals and turn them into a formal project description giving a summary of the goals and how they relate to all the values that is less than 400 words”

I am still trying to pull apart the sentence “By promoting environmental and economic sustainability, we are encouraging the use of existing resources and fostering community-mindedness.” Something I’ve noticed about AI-generated content is that my mind slides off it like water. More on why I think this quality is so dangerous later.

The content is actually great when what you want is bullshit though! The scripts for YouTube videos promoting the project are pitch perfect (which isn’t to say they are necessarily good).

The video opens with a shot of the exterior of the makerspace building. The camera then cuts to a shot of a faculty member sitting in front of a desk with a computer on it. He speaks directly to the camera.

Faculty member: "Welcome to the makerspace! I'm excited to share with you our new goals for the coming year. We've been working hard to create a tool library, a textile and fibre bank, and hire student sustainability champions to help our community learn, create, and innovate in a sustainable way. Let me introduce you to our makerspace staff and students who are going to share with you how these new initiatives will benefit the community."

The camera cuts to a shot of three makerspace staff members, who each speak in turn.

ChatGPT will make things up and leave things out

This has been much discussed but ChatGPT will happily make things up and more confusingly in this context it will also randomly leave things out. This means you need to spend a lot of time making sure it hasn’t made something up or left anything important out. For example, in response to the prompt 14 (“write a summary of the prompts and responses in this session using bullet point and 1-3 sentences for each prompt”) ChatGPT didn’t include several of the prompts in the session, even though it obviously has access to them.

Not only make things up, but it seems like the things it makes up become retroactively part of its history. In prompt 9 when I asked for a summary it made up a university name, and then later it re-integrated that name into its description of prompt 1 when I asked for a summary of the prompts we had used. I could imagine how quickly that kind of complex messy history re-writing could get out of control quickly.

Conclusion

I like that ChatGPT can take original content and transform it into a bunch of formulaic structures for me. I like coming up with ideas and brainstorming with people from my community, but I really dislike writing highly structured documents. I can also see the potential value in the generated ideas (e.g. planning committees, policies) it uses to populate the structures. Presumably if many other grant writers thought these kinds of ideas were worth including I might want to think about including them as well.

I worry though that people will become anchored to the (glib, bullshit-ish) ideas that AI generates and have a hard time setting them aside. These ideas come from a corporate language model trained on parts of the internet and reflect the biases of that data, they don’t come from anyone’s community. Users of AI might end up implement them even when they aren’t appropriate.

What worries me more is that on a brief skim many of the ideas generated by ChatGPT (e.g. the links between goals and institutional values and metrics in this example) look okay, especially in the context of all that structure. You would need to read carefully to catch how often they are glib or bullshit ideas. Bullshit can trick people, especially tired or disengaged people. Worse, as I said earlier I find my mind resists engaging deeply with AI-generated content. Carefully structured documents currently require a lot of work to create and therefore are a gate (for good or bad) that people need to pass through. In a world where in a few minutes anyone can produce a beautifully formatted 20 page project plan that references organizational values and policy, will our social structures (committees, etc) be able to disambiguate what is actually good from what just looks good?